This review contains mild spoilers.

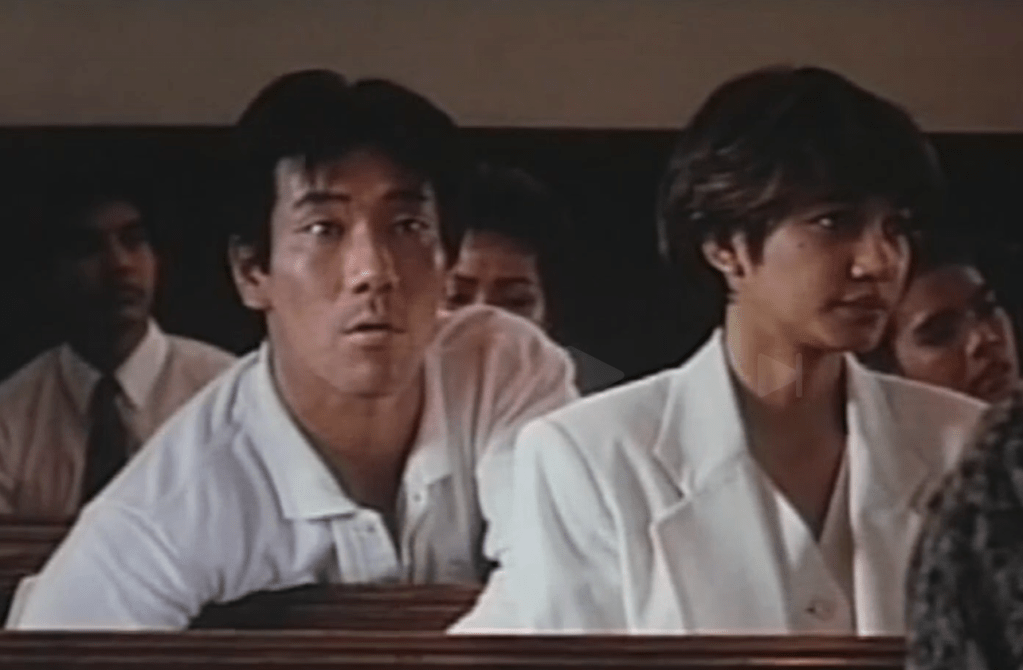

Man commits a crime for the sake of his beloved is a tale as old as time. But Takeshi Kitano took this familiar narrative and flourished it with painful, understated, and at times violent beauty to set off a spectacle worthy of the title Hana-bi (Japanese for ‘fireworks’), his Golden Lion-winning 1997 masterpiece.

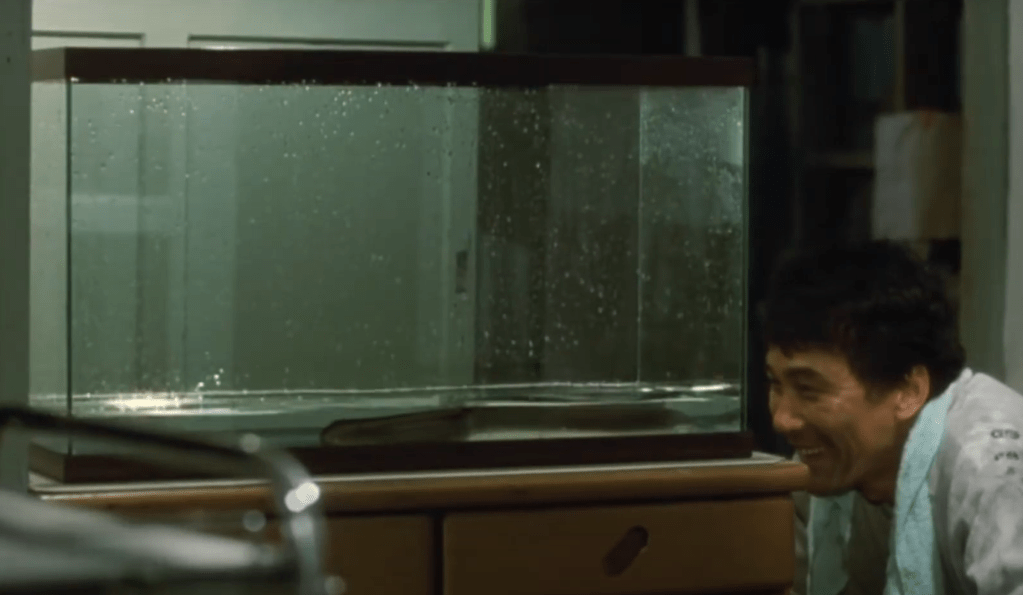

The title itself reveals two of the film’s prominent motifs: flowers (花, hana) and fire (火, hi/bi), more specifically, gunfire. Hana-bi, usually tagged as a “crime drama” in reviews and synopses online, almost fetishizes these motifs if not for the curious and quietly visionary way that Kitano directed this work.

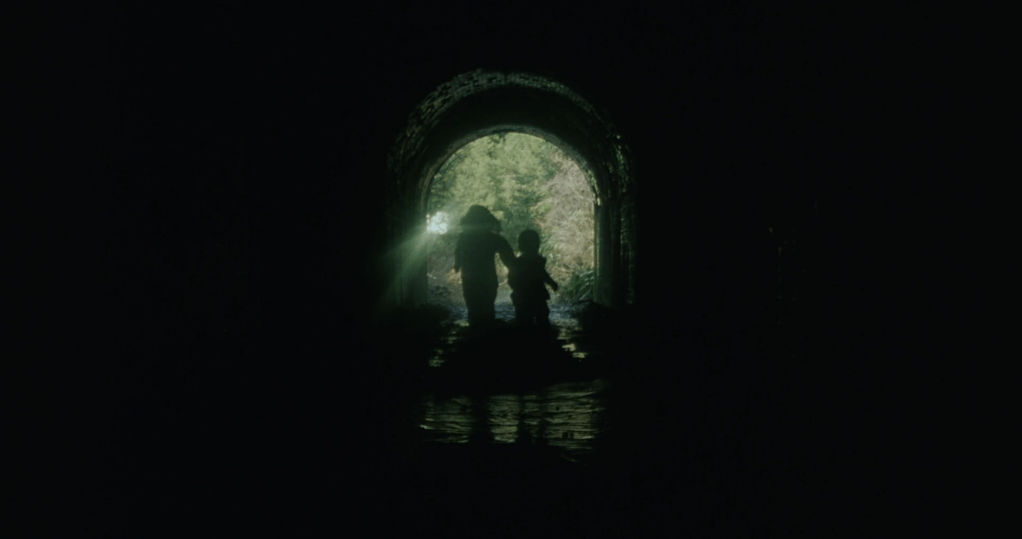

A great example of what I’m talking about is a scene in the film’s second half where the camera pans over a painting of tiny yellow flowers that are also the kanji for “hikari” (光, ‘light’). It then zooms out to reveal the flowers falling into a serene snowscape. The calmness is jolted when the word “suicide” is revealed to be painted in big, bold, scarlet kanji, marring the pure landscape. The film then moves to a bloody real-life scene, before returning to the painting, now splattered with scarlet paint as a character pulls the trigger of an unloaded gun. This seamless blend of serenity and violence, present throughout the film, culminates in a finale that is one for the books.

My thoughts on this film wouldn’t be complete without mentioning Joe Hisaishi’s score. I might be biased because I am such a big fan of his wonderful work with Studio Ghibli. But it was so satisfying to hear a familiar style right at the opening sequences and be pleasantly surprised to see Joe Hisaishi’s name as the scorer. Hana-bi, it turns out, was already his fourth collaboration with Kitano.

The effect of Hisaishi’s score is heightened by how camera movements were so sparse that even “action” sequences were stylistically plain. With this, the score became instrumental in dictating “movement” and not just mood. It was equal parts pensive and brooding, giving the feeling that something is brewing that will explode and shock.

And shock it did. The ending is as ambiguous as it gets, leaving the audience postulating what happened. And in that final shocker lies the X factor as to why this film is a cult favorite, in the vein of Fight Club. Hana-bi seemed to have treated death and violence flippantly, but it is not a film to teach about morals. However, it is not hollowed of substance, either.

Indeed, in Japanese culture, the word used for the phenomenon called “double suicide”, shinjuu, is formed through the characters for “heart” and “center/inside” (心中), reflecting the inextricable link between the participants of such sad endeavor. It’s an open question whether this was the fate of some of the characters, but such oneness reminds us that life and death, and beauty and violence, are not just intertwined—they are inseparable.