There is no doubt that Hirokazu Kore-eda has mastered both the form and substance of cinema, developing a distinct visual style that elevates his deeply humanistic storytelling. While films like Maborosi (1995) showcase his technical mastery of the cinematic form, and Nobody Knows (2004) and Monster (2023) reflect the breadth of his narrative and thematic ambition, Our Little Sister (2015) stands out as one of his most intimate, character-driven works, supremely centering on people and relationships more than plot or message.

As with many Japanese films, the original title—Umimachi Diary—differs from its English counterpart, possibly to appeal more to Western audiences. Regardless of the reason, both titles offer rich lenses through which to understand and appreciate the film.

With “Umimachi Diary”, (‘seaside town diary’), the film highlights the importance of rootedness not only in personhood but also in relationships.

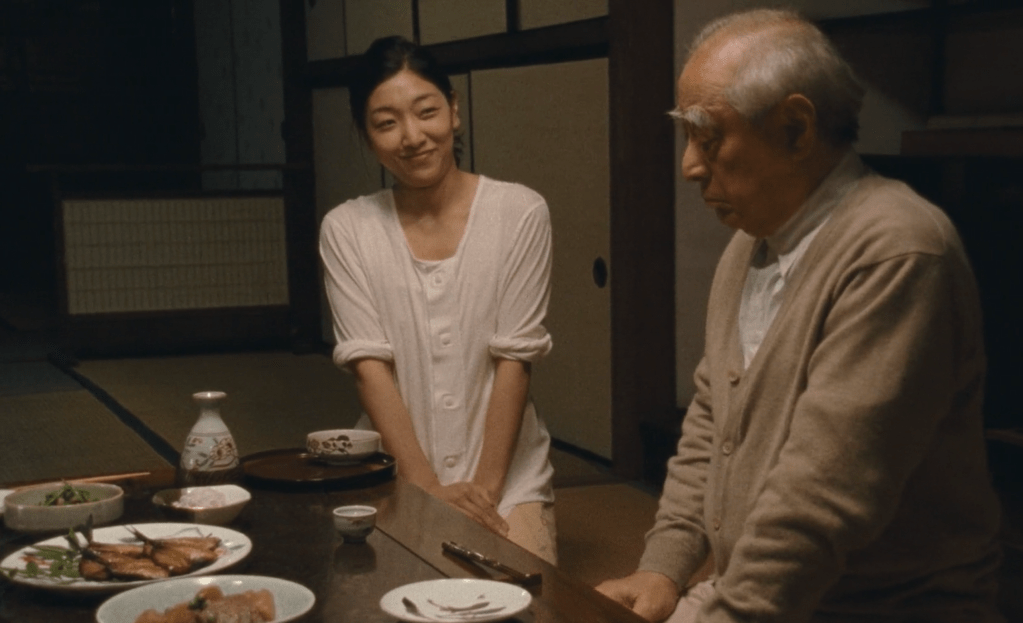

The film probes how the placeness of towns and their spaces such as cafes, houses, and temples have shaped the lives and connections of the people dramatized in the movie across generations. This is exemplified in the way the supporting characters influence the sisters’ lives, especially through gestures and encounters made possible by the unique rhythms and intimacy of a seaside city like Kamakura.

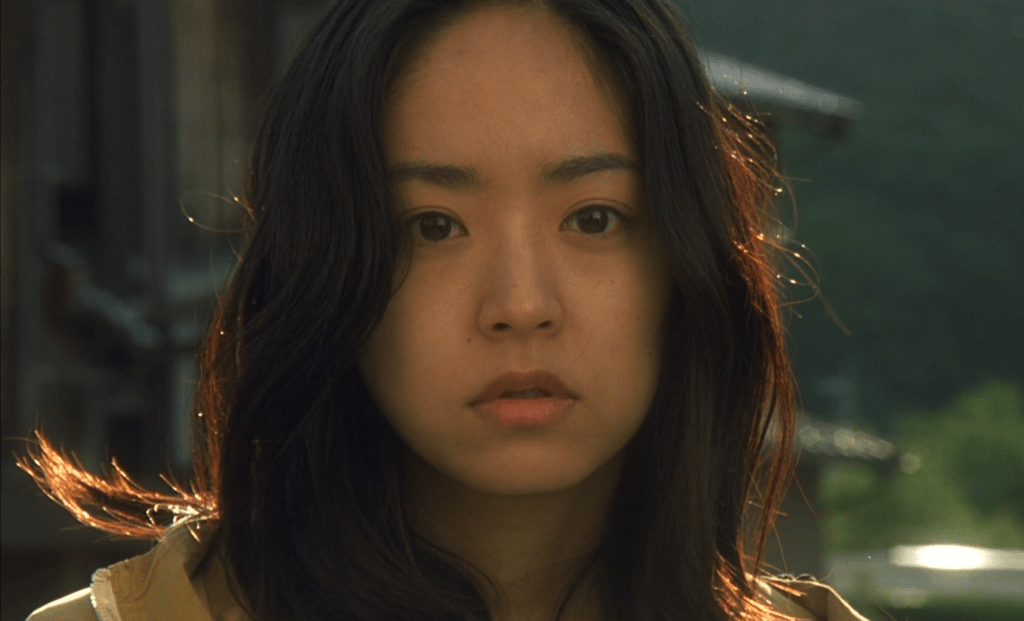

In contrast, the English title “Our Little Sister” draws attention to Suzu, the titular character who was adopted by her three half-sisters from Kamakura, after the death of their father who she cared for. In the film, Suzu was not just a character—she becomes the lens through which the inner lives of the others are poignantly revealed.

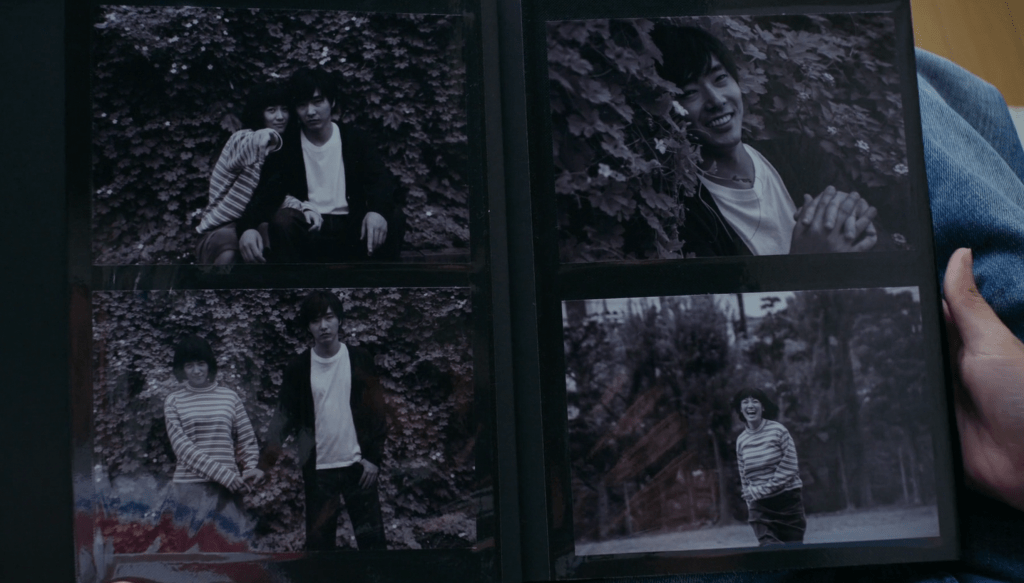

Like a prism, Suzu reveals the true colors of the nature of the various relationships in the film: among the three sisters Sachi, Yoshino, and Chika; between them and their late, estranged father; and especially between Sachi and their distant mother. And while Suzu was not in any way asked to resolve the issues that arose because of her presence, in many different ways her life, memories, and words affirmed the humanity of those she interacted with no matter what they were facing.

Our Little Sister has been the most moving Kore-eda film for me, getting the same impact even after many rewatches. It is in fact my most favorite film of all time, a movie I go back to for the comfort it gives me.

It’s beautiful in a way that it doesn’t manipulate emotions. Instead, it illuminates them. Our Little Sister shines a light on a rare kind of relationship these days—one ruled first not by love, but by grace. While I always thought Suzu to be the protagonist of this film, I realized that this story is as much as hers as it is the story of the eldest sister Sachi. Suzu is made to feel she belonged and loved not for what she might become, but for who she already is. Behind that welcome is Sachi, who, despite carrying her own burdens, offers Suzu grace. In one quiet scene, as they gaze at the beautiful sea together from a hilltop in Kamakura, this grace was in full display.