I want to begin by saying that it will not be difficult to point out who the namesake villain of the movie is if we base it on the efficient cause of what happened to the victim. If that’s the whole story, the film would’ve ended at about the halfway mark. Thankfully, Sang-il Lee’s 2010 Best Film awardee (Mainichi Awards and Kinema Junpo Awards) is not just about a villainy or even villainies, but so much more.

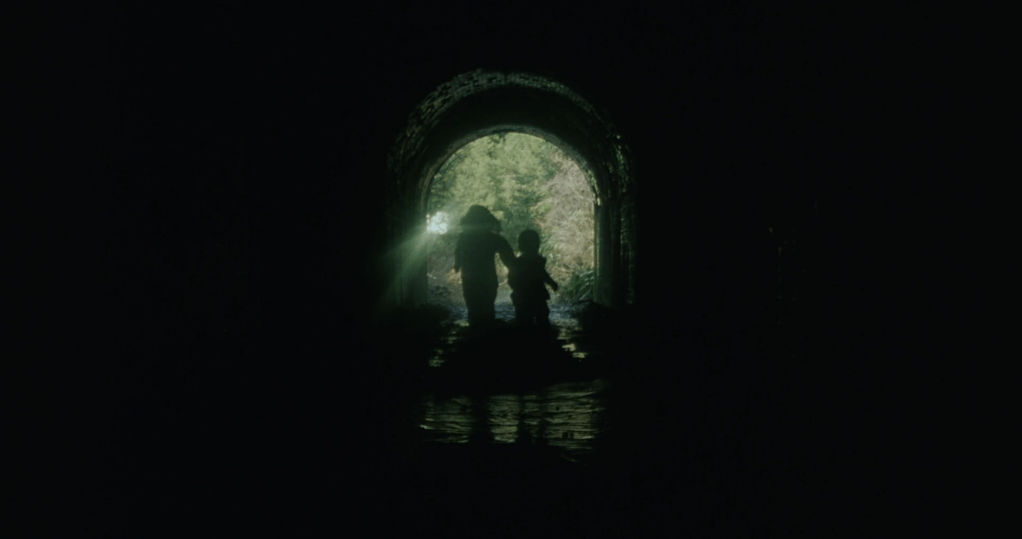

On the surface, Villain is a very competent and entertaining thriller that will keep the audience glued to the screen despite a slow start. It even makes a more-or-less substantial exploration of what really makes a villain. But it’s different from the usual crime-fugitive fare with how it rises above the conventions of its genre to explore a universal and almost unique human ability: the capacity to cherish another human being.

While the visual style is not necessarily “meditative” (e.g., lingering shots, long takes, sparse camera movements) this film is indeed a meditation on what the act of cherishing does to the one who cherishes. I am careful to highlight this because narratively, it’s easier to show the things that the one who cherishes does to the cherished (not that that aspect wasn’t also explored by the film).

For Villain, cherishing reveals our true selves and, in the process, changes us.

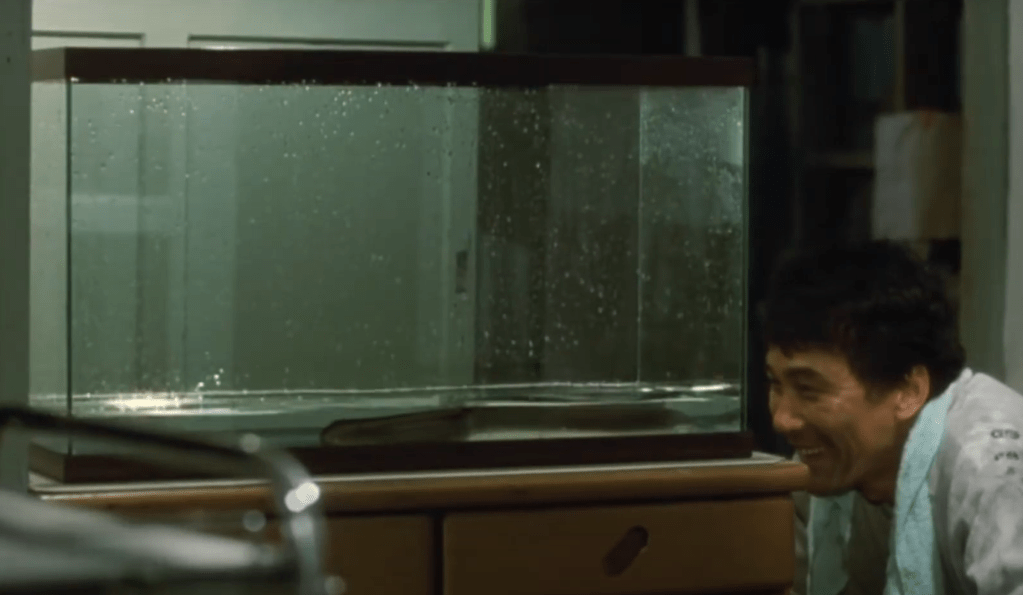

This exposition stands on the heart-rending performances of Satoshi Tsumabaki and Eri Fukatsu, Tsumabaki, in particular, as the uninspired young man Yuichi, delivers an engrossing character study in a role that is at once familiar and strange. Yuichi’s central inner conflict, the unquiet specter of his own depravity as his affection for Fukatsu’s Mitsuya grows, produced some of the most intense scenes in the film, including the most emotionally charged sex scene I’ve seen so far in Japanese cinema.

Veterans Akira Emoto and Kirin Kiki also delivered in their supporting performances as the father of the victim and Yuichi’s grandmother, respectively. Their stories of cherishing are underscored by loss—unjust loss of a beloved daughter, and the loss of a grandson to waywardness.

I wouldn’t miss mentioning how surprised I was again that Joe Hisaishi did the score for this film. As with Hana-bi, I was clueless about his involvement here but unlike in that movie, I wouldn’t have guessed that it was Hisaishi who wrote the music for Villain.

Listening to the score on its own, which also includes the closing credits track Your Story, I wouldn’t have guessed that it was the score for a crime movie (one reviewer even described it as “a soothing treat”). Equal parts contemplative, foreboding, sweet, and wistful, the score underscores what I think is the main point of the movie as I’ve shared above: that cherishing and loving someone reveals your humanity, including your depravity, and changes you along the way.