This review contains minor spoilers.

I’ve never seen a film with an ending as excruciatingly painful as it is quietly tender, as Hirokazu Kore-eda’s 2004 childhood abandonment drama Nobody Knows. Yet even the word “drama” might be overdoing it, for this scandalous film burdens its viewers with the weight of reality in such a dignified and constrained manner.

“Nobody knows” speaks about the fact that save for a handful of people, nobody really knew nor cared, about a very young brood after their mother went missing-in-action.

This is in stark contrast to how the audience is burdened with the full knowledge of the brutality of parental indifference to what is supposedly the most crucial phase of human life. The result is a film that implicates the viewer with a sense of responsibility for a reality that they might never encounter in real life, made all the more devastating in its quiet, matter-of-fact portrayal.

Kore-eda’s signature storytelling techniques work particularly well here to evoke such contrast. Harking back to his days as a documentary filmmaker, he presents the charming but messy domestic life with children using a grounded and unadorned style, almost like reportage.

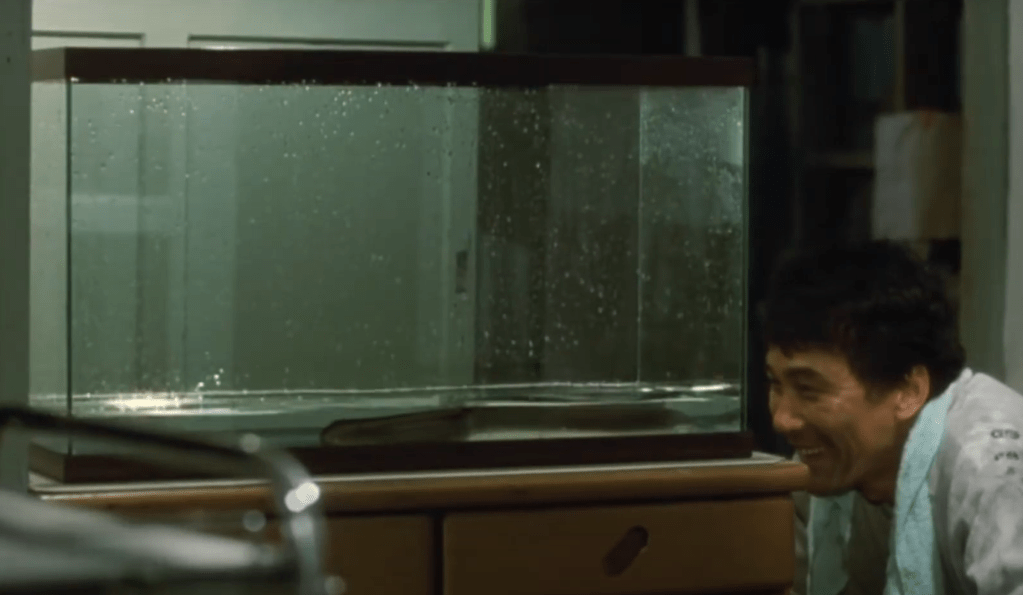

And then there’s Kore-eda’s use of mono no aware, a uniquely Japanese sensitivity to the impermanence of things, to evoke in the film a strong sense of vulnerability, frustration, and eventually, resignation. This is mainly showcased through the recurring juxtaposition of extremely tight shots of the children and inanimate objects such as toys and household implements, as if the objects mirror the children’s emotions. Together with his trademark lingering shots, Kore-eda used that visual motif to intimately portray innocence, and then later, innocent pain.

Another study in contrast can also be found in the protagonist Akira, in an award-winning portrayal by Yuya Yagira. Akira is the classic “child who grew up too soon”, learning to have that perceptive look of a mature adult at a very young age. But the most excruciating aspect of his performance is the painful conflict between irreconcilable desires: on one hand, to be a responsible oniichan to his siblings, and on the other, to live a boyhood so ordinary it’s extraordinarily out-of-reach for someone in his situation.

There is a minor story in the film where the children get to take care of their own individual plants after a particularly happy event in their confined lives. What would’ve been a teaching moment in responsibility, something that parents would want to give their children early, quietly devolves into a symbol of decay and neglect as the physical effects of parental neglect of them becomes inescapable.

With this, my final thoughts go to the contrast between Akira and his mother. Not only was she absent, but in her brief appearances, she is patronizing, evasive, and emotionally manipulative. As it is, the film is already tragic, but what’s more devastating is how her irresponsibility was not just in her neglect, but in her refusal to grow up—even as her son was cruelly forced to.