It’s not an easy feat for a film to be lengthy, entertaining, and profound all at the same time. Yet Momoko Ando’s 2014 masterpiece 0.5mm is all three, and then some.

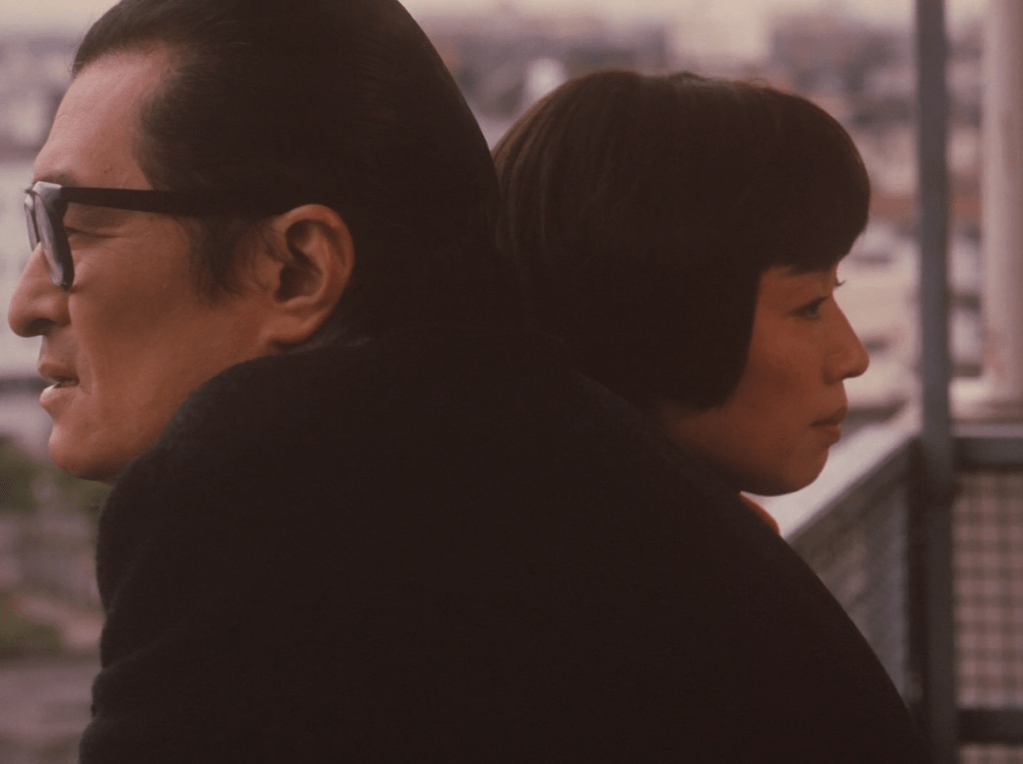

With a runtime of three hours and 18 minutes, this film is expansive not just in length but more so in its thematic ambition. 0.5mm is a singular achievement not only for Ando, who is both the film’s director and screenwriter, but also for her sister, Sakura, and her ineffable and career-defining take on the caregiver-vagabond Sawa Yamagishi. Sawa embodies a certain “lightness of being” that, contrary to the title of the famous novel, is not unbearable. This lightness extends to the whole of the film itself, so that it is both profound and outrageously funny.

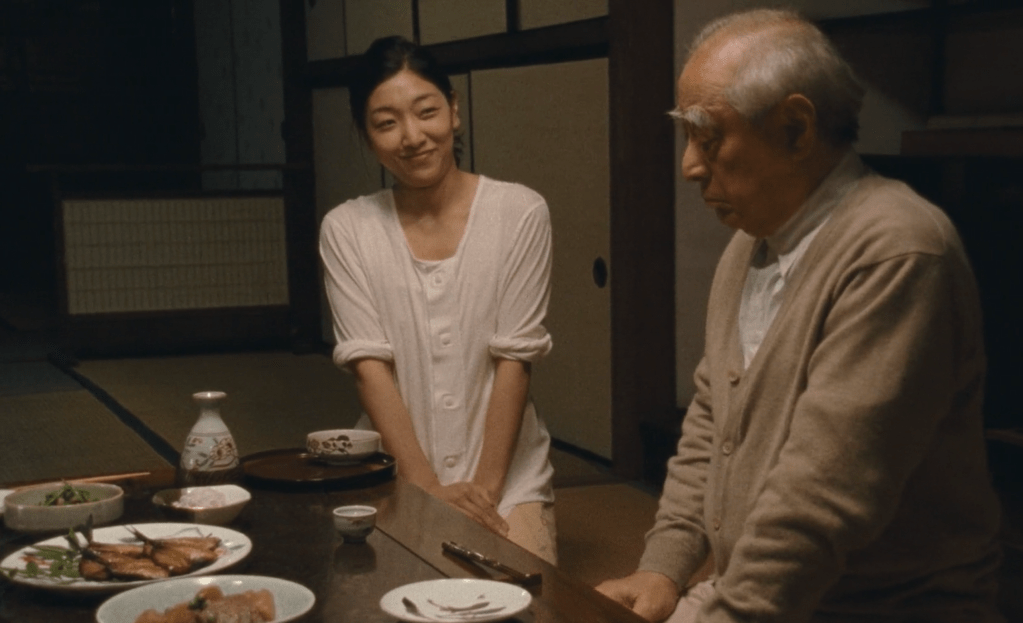

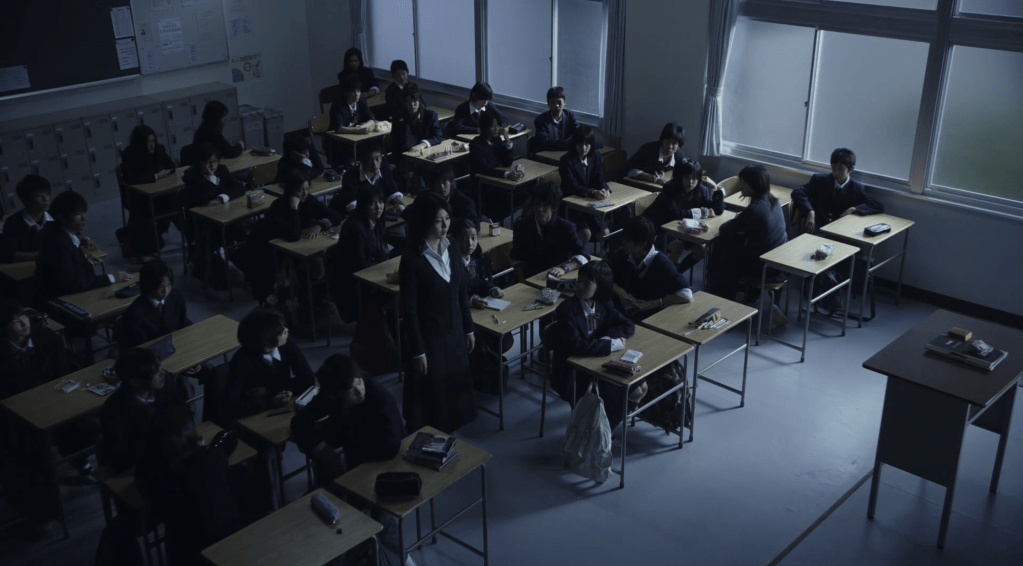

Set, it seems, in the late 1980s to the early 90s, the film is divided into four parts: a prelude where Sawa is introduced as a caregiver of a bedridden elderly man, two acts where she would live with and care for two other elderly men, and a final act of resolution that harks back to the prelude. Throughout, Sawa’s character moves through the film with what I’d call “buoyant grace”—unattached, adaptable, and at times, mischievous. But while she is physically a drifter (and a mysterious one at that), she is not aimless.

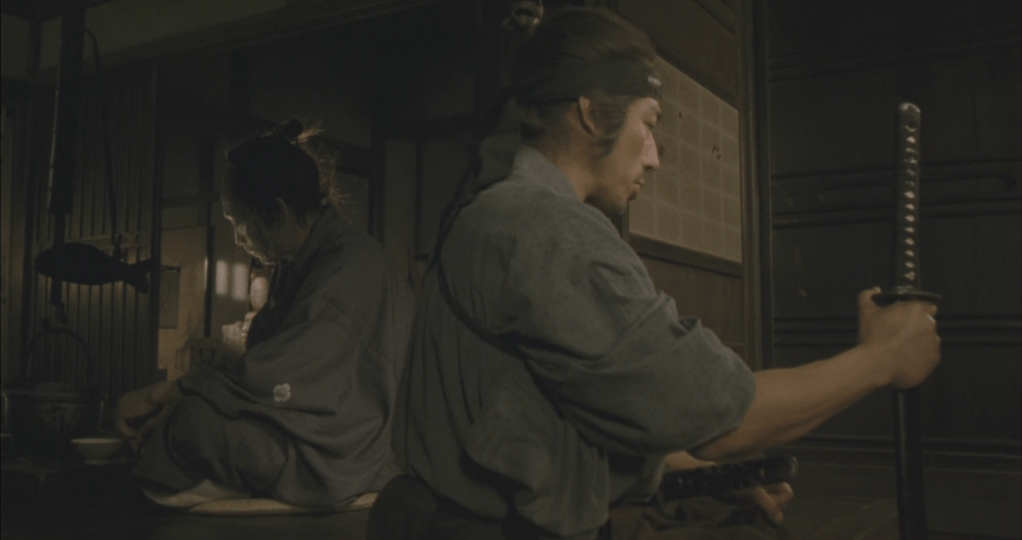

Sawa is not just a character—she is also a remarkable narrative device by which the film becomes an epic and complex meditation on human connection, the loneliness of the elderly, and the strange forms that kindness can take. It is through Sawa and her relationships that seemingly disparate themes such as the war nostalgia of elderly Japanese men, the collective versus the individual, the male gaze, and the kindness and seductiveness of a woman as both wife and caregiver come together and come alive.

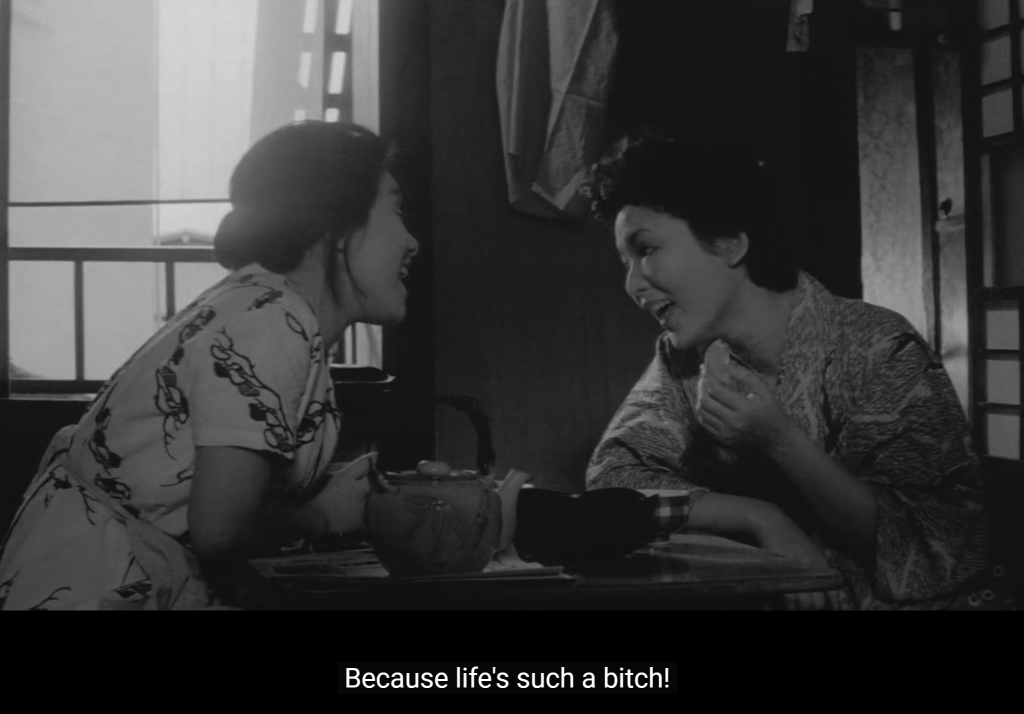

Among those themes, the latter two are particularly prominent. They could’ve been touchy subjects, if not for Momoko’s writing and Sakura’s acting. Their collaboration made for a deft portrayal of how a woman makes peace with society’s patronization and misogyny, subverting them to gain power that is not only seductive but more crucially, substantial, generous, and real.

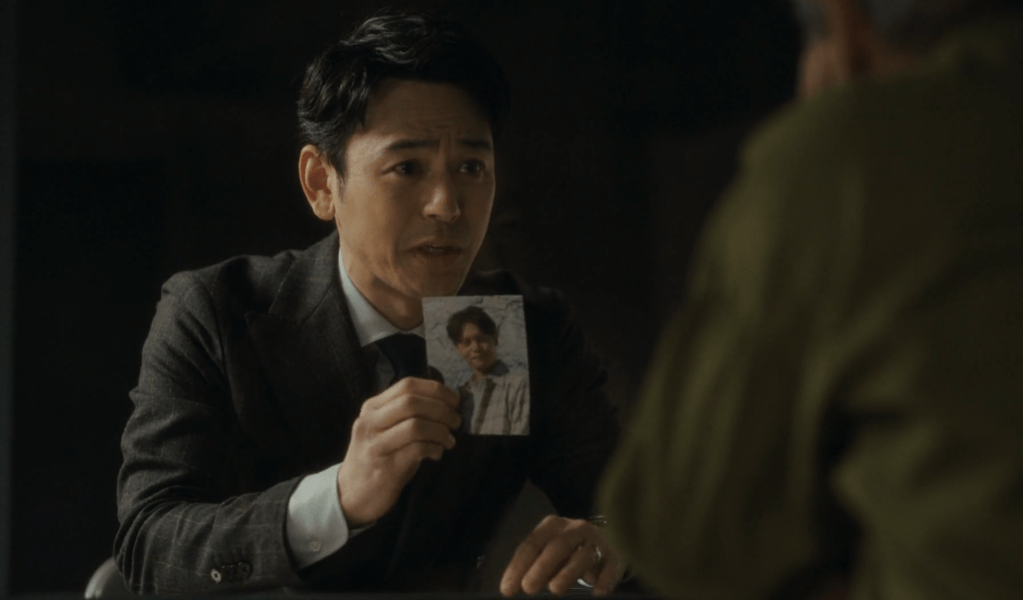

Sawa’s “feminism,” if you could call it that, is not vindictive nor activist—it’s human through and through. One recurring incident in the film highlights this. Sawa’s drift, it seems, is to catch elderly men in scandalous, reputation-wrecking moments and use these to “coerce” them to let her live with them. However, she would use the power she gains not to extort nor to persecute, but to care, quite literally. In each case except the prelude, Sawa brings and inspires order and healing in the lives of the elderly men she was involved with.

I may have made Sawa sound extraordinary, but what lingers most is her plain, unadorned humanity. She feels like a mystery only because tenderness and generosity have become rare. 0.5mm is special for letting that quiet humanity shine.