It’s not all the time that you come across a movie that’s thoroughly and genuinely entertaining and at the same time an empathetic, grounded, and most importantly, relevant commentary on contemporary society.

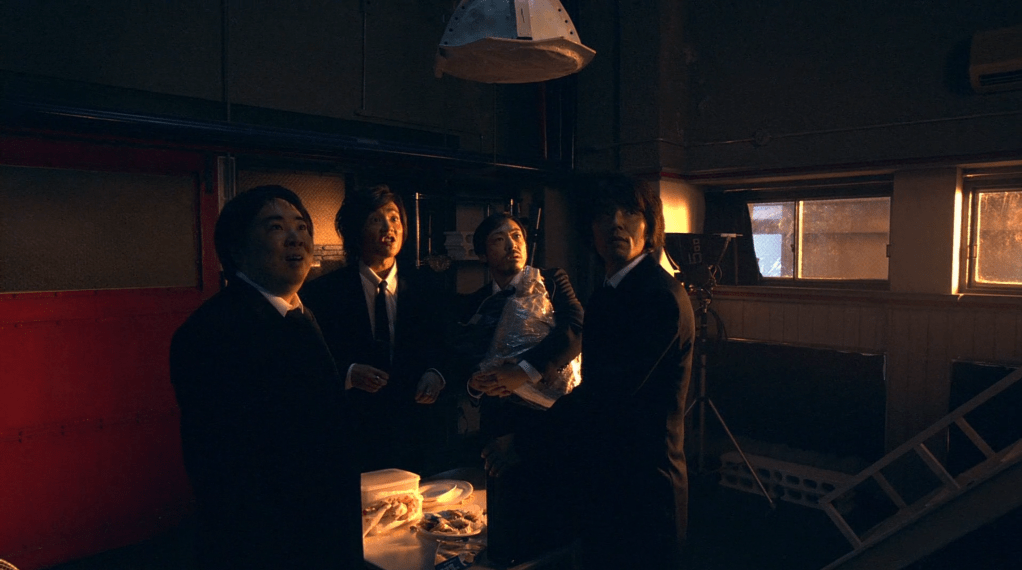

Kisaragi is both. The entertainment aspect is hard to miss and it’s built within the premise of the movie. Five die-hard online fans of Miki Kisaragi, a low-level idol who allegedly committed suicide, decided to meet in-person for the first time to commemorate her 1st death anniversary. The commemoration quickly evolves into an “investigation” into whether she really took her own life. Twist after twist about the incident and the true identities of these “fans” made for a wild ride in a rollercoaster of emotions, one that is not shallowly contrived and is consistent to the emotional core of the whole movie throughout. That it was 2007, during the era of nascent social media, when online social fandoms were also only gaining ground across the world, make for a curious context that will have viewers amused at the idiosyncrasies of online interactions between fans during that time, and at the same time, realize that some of the same fandom idiosyncrasies still exist today.

And there also lies the potent social commentary that Kisaragi is. It’s thoroughly empathetic to the fan in that while it finds comedy in the very things that make fans fans, it doesn’t make fun of them. We will always find weirdness in other people, or perhaps, in ourselves, of the way we are as fans of whatever or whoever we are fans of, but Kisaragi finds the humanity in those things. It’s curious how the film has withheld the face of Kisaragi until the very end, because our initial instinct as viewers most probably would be to know whether this idol is beautiful and worth fawning over. But this is the commitment of the film towards focusing on the five fans, although it has its own commentary on the idol life as well as the parasocial relationship existing between them and their fans.

I love how by the end it was completely satisfying both as entertainment and as an introduction to fandom culture. But aside from these, the film also leaves you with questions to reflect on after. Things like, how much influence do fans exert over the intensely personal aspects of idols’ lives, or what kind of expectations are fans entitled to from their idols. Japan, even before the world got into K-Pop and such, had a very strong idol scene that has attracted legions of fans and gave birth to phenomena such as “herbivore men”. An appreciation of this film would therefore be more complete with those aspects in mind.