I don’t often feel so strongly about narrative direction in films going the wrong way, because stories are expressions of creative freedom and I think the respectful way to go about it is a matter of preference (I did like it) and not of correctness. But that’s definitely what I felt after watching It Feels So Good, Haruhiko Arai’s 2019 banger of a film (pun definitely intended) about two former lovers who agreed to temporarily rekindle their passion before one of them set out to get married.

There’s a lot to like about this film, not the least the depiction of sex, which was deftly acted by Tasuku Emoto and Kumi Takiuchi. I don’t usually go about seeking to watch erotic films, but I can say that the physical realism and believability of the intimacy scenes are some of the best I’ve seen in film. It’s not prestige sex of airbrushed skin and cheesy soft lighting—there’s a lot of humanity portraying the “messiness” of getting to and doing it, which adds to the carnal appeal of the scenes. Even so, nothing was gratuitous.

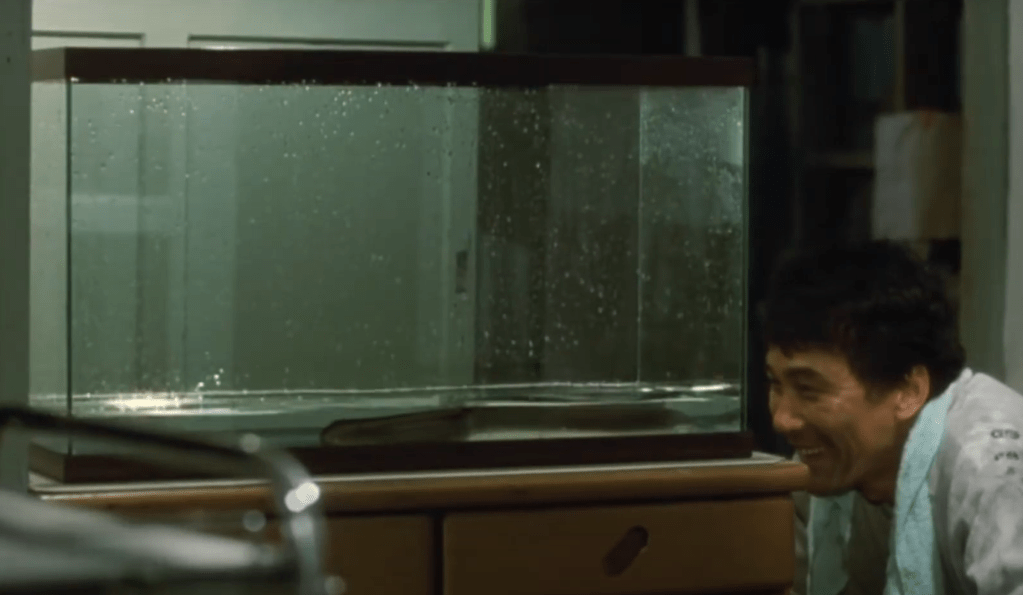

And while the sex was very visual, the keyword that governs the viewing experience of intimacy is feeling. There’s the feeling of power that the woman has over the man. There’s the emphasis on rawer physical sensation, with the camera trained on whole bodies doing the act and faces contorted to unabashedly display pleasure.

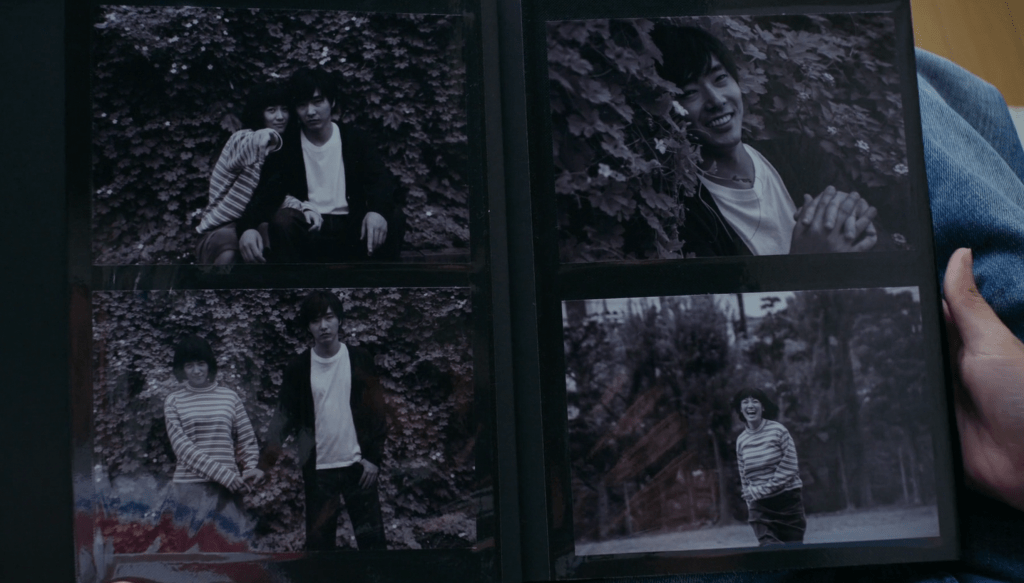

And despite the more controversial and taboo aspect of the sex (hint: “blood is thicker than water”), there’s pervading feeling of comfort of being with someone from your past that comes through to the viewer. Indeed, there’s a lot of nostalgia, both happy and wistful, in this movie: from memories of childhood, to memories of young adulthood in the city, to the devastating memory of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake.

Which is to say: this film is a moving reflection of that great disaster from a very personal and intimate point of view. For the protagonists, their intimate reunion is a powerful affirmation of life, being alive, and perpetuating life after devastation. It initially felt jarring to me, but after watching this film, I now strongly feel that the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and the disaster it wrought is something that is deeply ingrained in the contemporary Japanese psyche in ways that much of the outside world hasn’t fully grasped yet. But this film showed how bodily convulsions and tectonic tremors can be combined in one potent narrative.

Which leads me now to that unceremonious end to what could’ve been a 5-star film. It might be the obsession with disaster, but it truly seemed overkill that the film doubled down on an already effective message about its personal effects with an amateurish narrative turn.

I can only liken it to the festival dance featured in the film, depicting the wandering spirits of the dead that cannot enter heaven—full spiritual consummation. The film was almost there towards a sensible resolution, but unlike the two protagonists many times in this film, it just didn’t come.