Earlier this year, I binged-watched Asura, Hirokazu Kore-eda’s latest work which is a limited series on Netflix (7 episodes). To me this is a much more impactful work than his other Netflix series, The Makanai, both in terms of the story and the depth by which the story is told and made to affect viewers. I can say that as a director, Kore-eda’s humanistic style and talent really shines in a (TV) series because he is able to flesh out characters and relationships much more fully than in a film.

Coming at the heels of a rewatch of Our Little Sister, I can’t help but compare the two to each other (because of how the stories have many similarities aside from the fact that they revolve around four sisters) and to Kore-eda’s other works that I have seen so far.

To those who have watched even a few of his works, it is obvious that Kore-eda is able to portray humanism very naturally in his films, especially in directing characters and the dynamics between them. It strikes me how much drama and clarity of emotion can be had in subtlety–whether because of the reservedness of Japanese culture itself, or Kore-eda’s direction, or both. This is opposed to how humanism is sometimes forced in more plot-driven stories, especially in Filipino films (from where I come from), which always appeal to poverty or political/cultural/structural curses, etc.

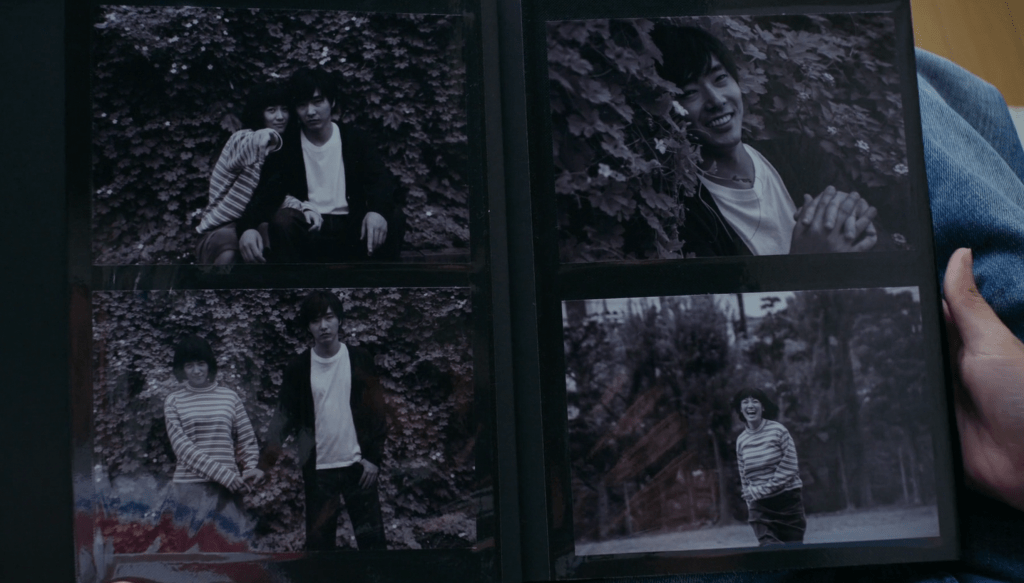

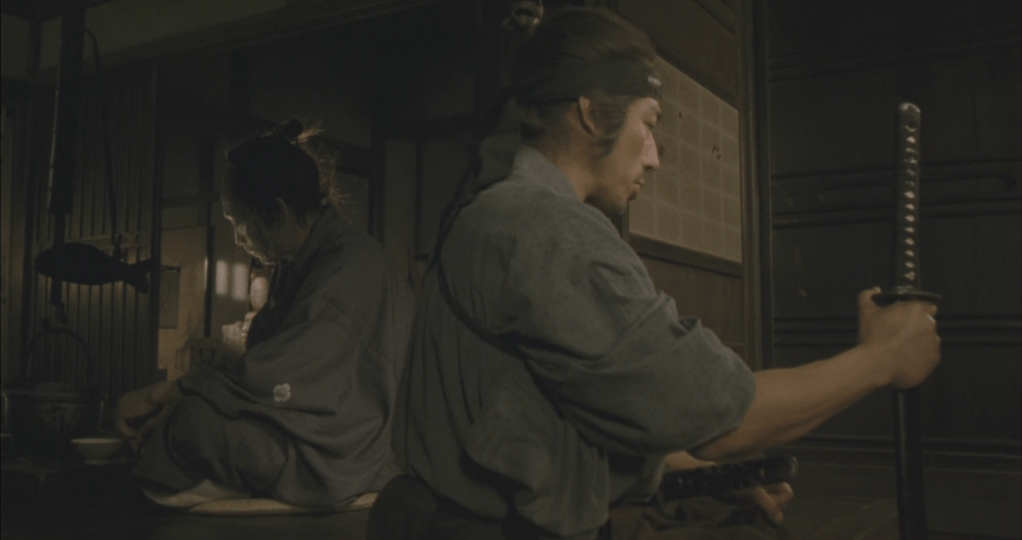

In both Asura and Our Little Sister, I love how Kore-eda directs the scenes of the four sisters together. Each pair of sisters, particularly the Tsunako-Makiko and Takiko-Sakiko pairings in Asura, have their own dynamics when they are together that are deftly made to come alive on the screen by Kore-eda and the sister ensembles.

But the magic is when each of the four sisters in both works, even when they’re together in scenes, are still able to shine as their own characters. I have to give props to Suzu Hirose, the only actor appearing in both works, who has shown incredible range particularly in Asura. While it is a bit of a given that she will be a focus as the titular character in Our Little Sister, she held her ground well among the veterans in Asura, showing how much she has developed in her craft in the decade between these two works.

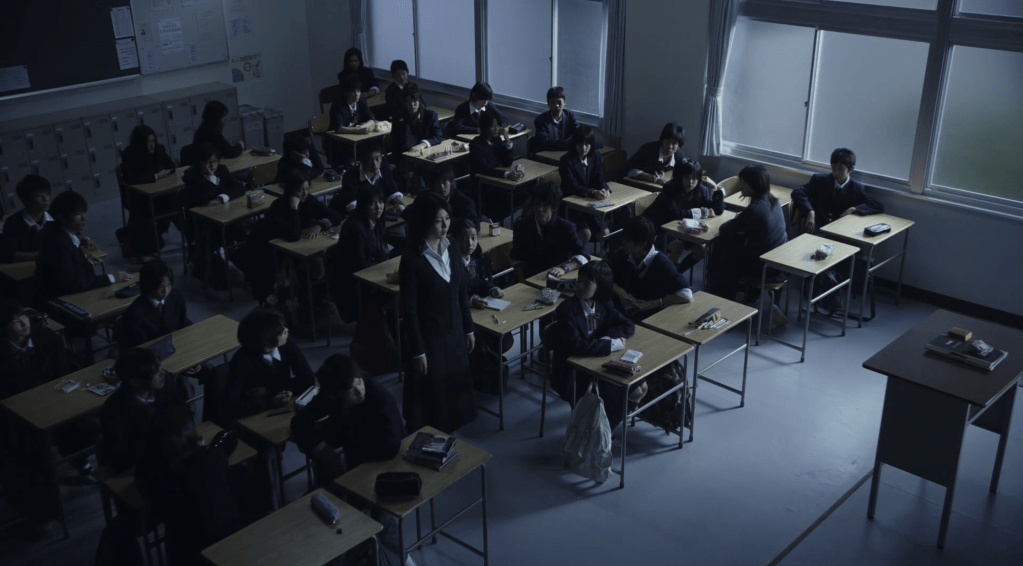

There’s this one scene in Asura, in the latter half of the series, when the whole family had to come to the ancestral home to sort an incident caused by the father which reminded me of a Hieronymous Bosch painting. When you look closely each object or character in this painting, something distinct is going on with or about it it. But when you look at the painting as a whole, everything comes together beautifully. Kore-eda’s blocking and choice of shots in scenes have the same effect in scenes that involve multiple characters.

Which lead me to a final point, about how there is not one emotional core in many, if not most, of Kore-eda’s works.

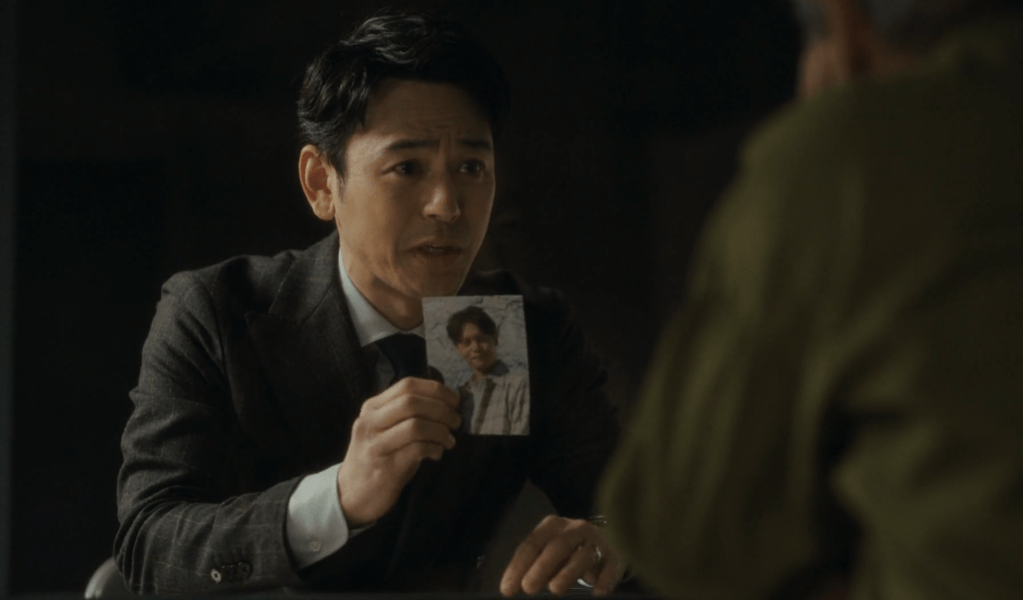

In both Asura and Our Little Sister, you can say that there are main plots and there are subplots, but nothing grand or forced–above all, it’s the kaleidoscopic complexities of being human that rises to the surface. It’s humanity of the characters driving the stories, not a big plot or other external circumstances driving the characters. There are themes, yes, for example, queerness in youth in Monster, poverty in Shoplifters, truth and law in The Third Murder, wrestling with grief in Maborosi, or finding your calling in The Makanai. These expose messages or morals, but through and through, it’s really the existentialist beauty that stands out.

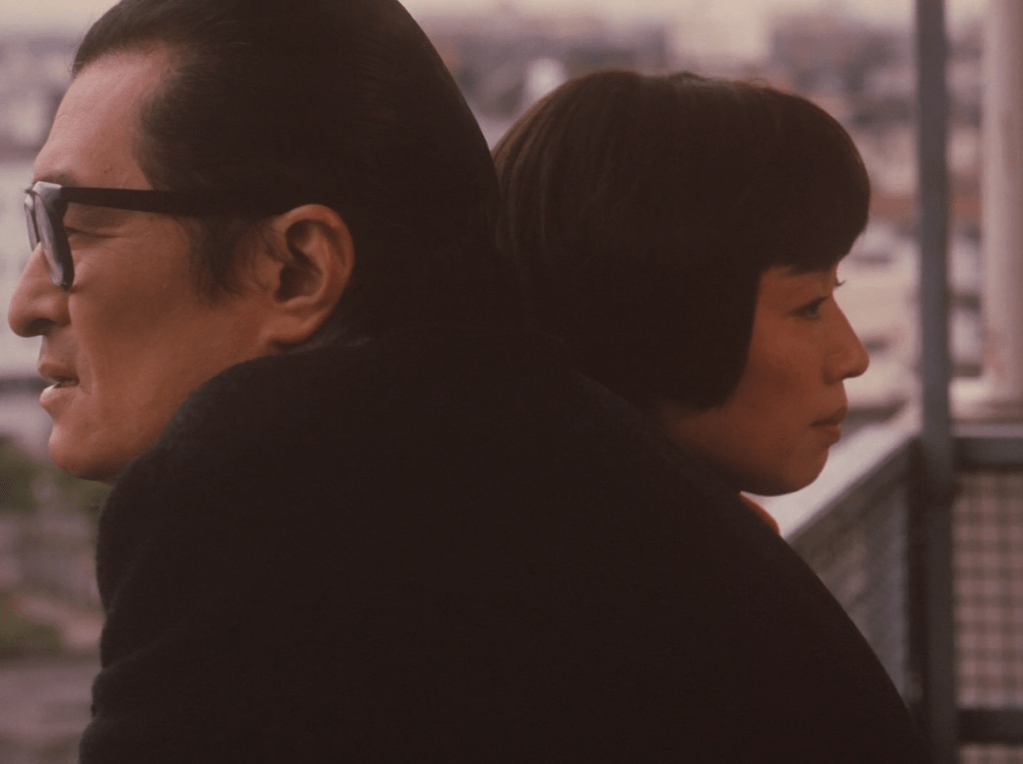

No wonder Kore-eda’s movies feel so grounded that some of his works almost feel like documentaries in their groundedness (he did work extensively as a documentarist). The slice-of-life production aesthetic and the almost meditative cinematography that he uses contributes to this existentialism—you almost feel like you live with the characters, if not the characters themselves, by how grounded to reality and the world the characters are. The effect of this is we see ourselves reflected in them in one way or another.