In films like this, where a central object of curiosity is highlighted by the title (in this case, the eel), it’s easy to become fixated on it and overlook other important aspects that deserve attention.

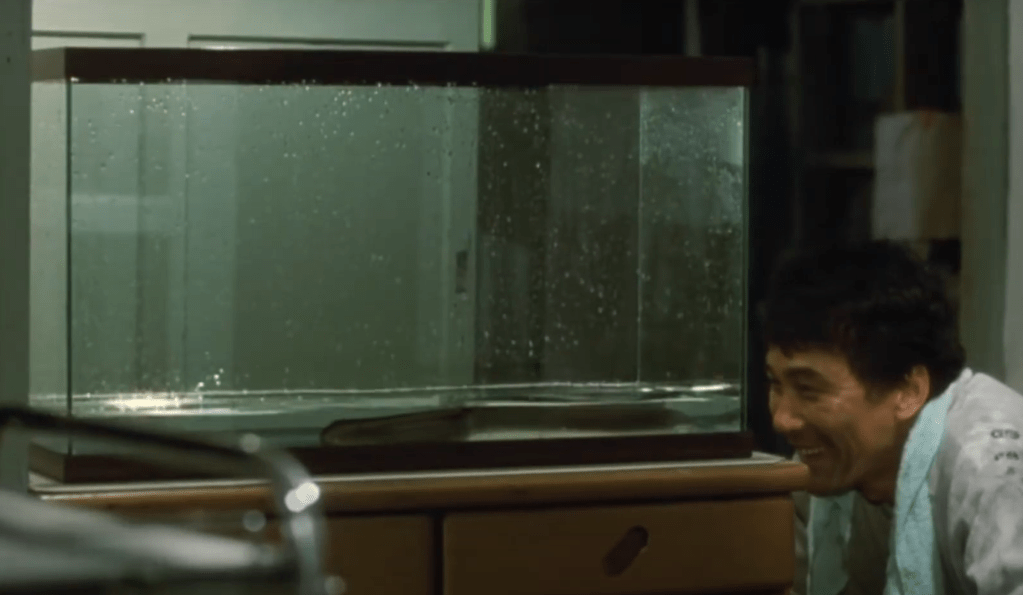

As I watched the film, I found myself consumed by the question, “What did the eel symbolize?” Was it simply a pet, a representation of the protagonist’s traumas, both external and self-inflicted? A symbol of his growth, with the eel embodying both his “before” and “after”? Was it his conscience or alter ego?

A deeper analysis could support all these interpretations, and indeed the eel itself warrants close visual and narrative analysis, as it’s crucial to the story. But The Eel deserves appreciation beyond its symbolism, as this Palme d’Or-winning work of Shohei Imamura shines in many other aspects.

This includes the powerful depiction of both honne (true inner feelings/true self) and tatemae (outward actions) by the lead actor, a young Koji Yakusho, who just recently (2023) won the Best Actor award at the Cannes for another film. Playing a former convict on parole, Yakusho was effective as the measured man who knew he has paid for his crime but is still racked up by the trauma of that past.

Imamura’s signature visual style also stands out, showcasing “rawness” within graceful compositions and well-blocked mise-en-scène. Much like in The Ballad of Narayama (animalistic passions alongside dignity in death), Vengeance is Mine (serial murder and incest next to gentlemanliness), or Black Rain (the grim effects of atomic bomb radiation alongside quiet rural scenes), The Eel juxtaposes orderly domestic life with bloody violence. Imamura, like the eel, can swim gracefully between these contrasts, making them into works of cohesive wholes that are still appreciated until today.

This style also allowed him to compellingly create what I think (so far, among the four that I’ve watched) is the film with most diverse set of characters. While depth could reasonably be expected only of a few of the characters given the restrictions of the medium, The Eel is able to provide a realistic response to the question of how a society reacts to ex-convicts in its showcase of a colorful cast of characters, all very human.