The English title of Izuru Narushima’s 2011 film, Rebirth, suggests a shedding of the past in pursuit of a new beginning. Its Japanese title, however, hints at a subtle, metaphor-rich expression of what the film is truly about, which I will return to later.

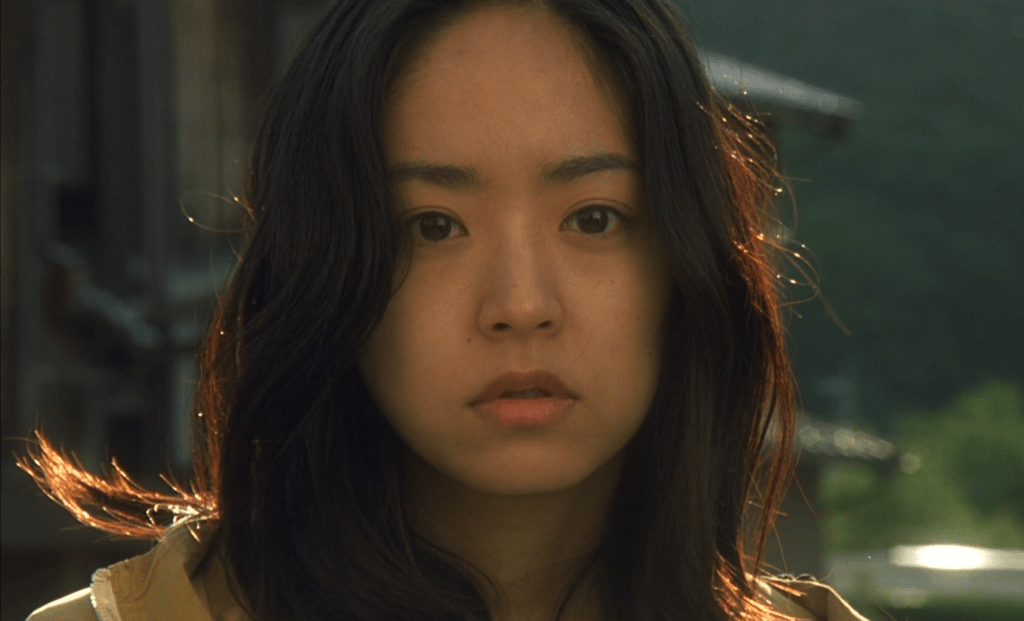

In this film, we meet Erina Akiyama (played by Mou Inoue), a listless university student who was abducted as an infant by her father’s former mistress. Her four-year abduction made headlines at the time. Now, she seems to be living a quiet, ordinary life—until a journalist eager to revisit that unfortunate episode seeks to resurface her story. Growing curious about that time in the distant past, Erina agrees to the journalist’s invitation to rediscover what happened then.

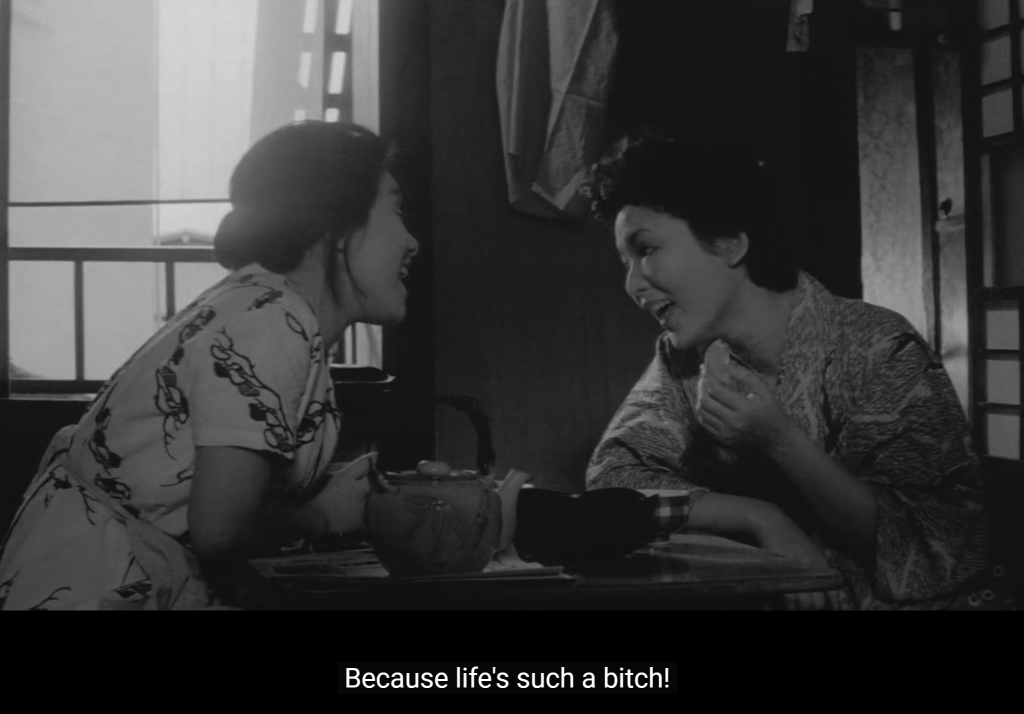

From the outset, the theme of motherhood is very prominent in the film, showing its pains and longings. Here, motherhood is denied, borrowed, and—perhaps most powerfully—chosen. Yet motherhood is but a part of a larger, more central theme, one that also captures the emotional–and eventually, the narrative–core of the film—self-discovery.

Since Freud, we have tended to think that our adult psychologies are invariably shaped by our childhood experiences and traumas. In Rebirth, we would think that Erina’s actual abduction or even her relationship with her “abductive” mother (played by Hiromi Nagasaku) would’ve made an enormous impact on her life. However, the film resists resting solely on this notion.

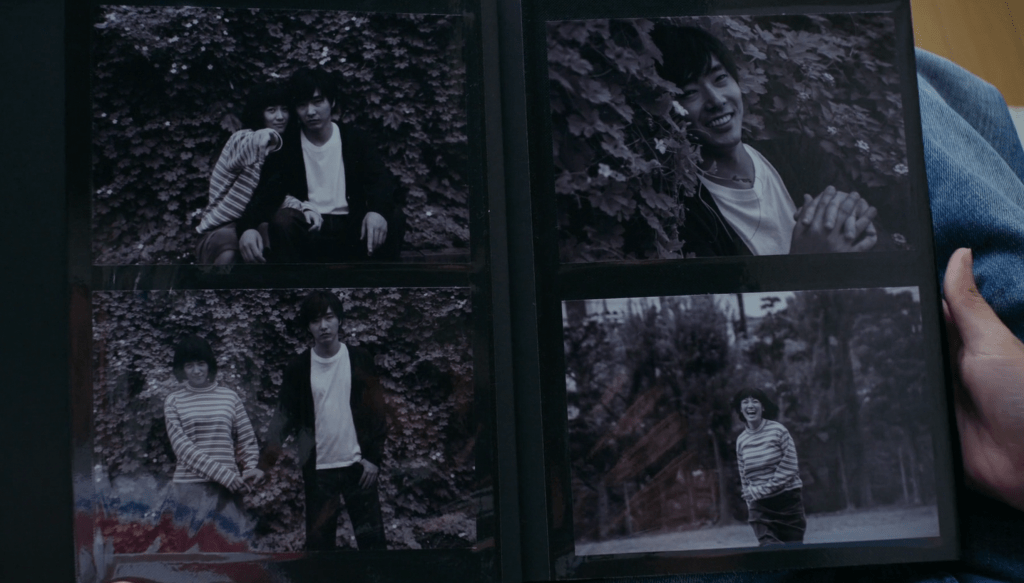

Rebirth emphasizes the outsized importance of the seldom-explored attachment to places and the memories of things that happened in them, whether good or ill.

This is where the visual storytelling of the film shines, as it proceeds to reveal Erina’s understanding of and feelings toward specific people, including herself, in its portrayal of places. We see the lonely townhouses in the uptown district where her parents’ house is, the enigmatic “shelter” where she and her abductor hid and stayed, and finally an island community of warmth and fulfilment that would later speak profoundly to Erina’s sense of being and identity.

Interspersed with flashbacks of sunlit scenes of a childhood lived in full on that island—joyous, vivid, but now, distant—Erina finds a reckoning in the present. Not against her abductor, nor her parents who resented how she grew up “absent”, but against a self that in every sense except the physical, in the throes of “death” and emptiness.

The film’s Japanese title, ‘Youkame no semi’, can be translated to “the eighth-day cicada”. It draws from the belief that cicadas live only seven days, after which they die together. While scientifically incorrect, it has been used as a metaphor for the shortness of life, shearing it of meaning. But the film quietly asks: what if one cicada decides not to die, and lives on for an eighth day—or longer? In the film, Erina not only decides to live but also to pay forward a life that has found new meaning and beauty.