“Ma, what other way is there?”

There is just so much to unpack from that remarkable line from another of Shohei Imamura’s masterpieces, the taboo-revelling The Insect Woman (1964), that I believe it represents both the narrative-thematic and emotional cores of the film. Imamura delivered through this film with his deftness not only with the black-and-white format but also with cinema’s unique language–editing. By combining masterful editing through the effective use of stills and a callback to the Japanese cinematic tradition of benshi, Imamura was able to showcase a masterpiece that not only unfolds in the viewers’ screens, but more importantly, in the fertile imaginations of their minds.

On the surface, The Insect Woman is a tale of survival and rising through the ranks, only to be met by the harsh realities of life after war and an unequal society. Sachiko Hidari is remarkable as the protagonist Tome, who played with such ease and depth the life of a farm girl-turned-prostitution madam in the fast-changing Tokyo of the 50s and the 60s. Tome’s life, as well as the lives of those around her—her daughter, her friends, even her lover and her family back in rural Tohoku—represent the life of insects, with its endless cycle of birth, growth, transformation, and death.

But is it just their lives though? We can answer this by looking more closely at the transliteration of the film’s Japanese title, “Entomological Chronicles of Japan.” To Imamura, Tome’s life is but a representation of the Japanese people and indeed, of Japan itself. Or is Japan really the “insect woman”?

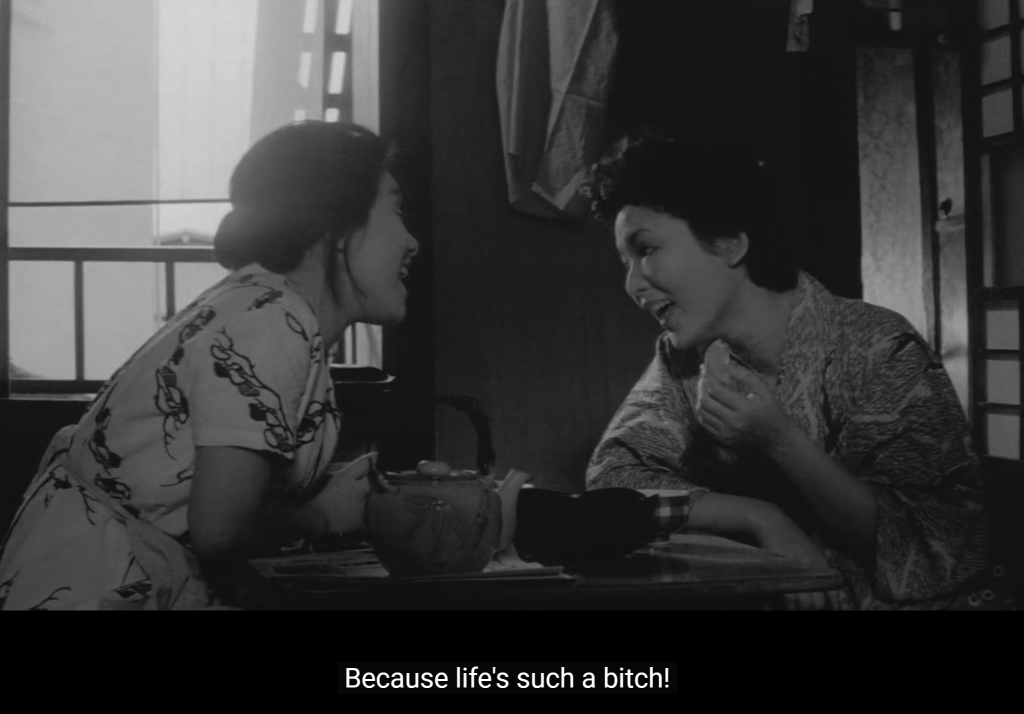

From the tailend of the Taisho period to the nascent years of the post-war Japanese economic miracle, the movie contends that nothing has really changed; everything but a part of a cycle. The sincerity of the religious is always undermined by the greedy. Women’s achievements are always treated as lesser and more easily dismissible. And sex, for good or for ill, is always a potent tool and path that women can wield to achieve a better life. Life is a bitch, Tome decried in the film, and bitching and being bitched on, whether literally or figuratively, is a constant throughout the film. The external circumstances might be in constant flux, but the substance of the Japanese psyche remains the same, a powerful thesis to make in a country that is proud of its newfound pacifism manufactured less than two decades removed from its imperialistic adventures.

That life is just a cycle of predictable phases, like that of an insect, can be downright nihilistic in its reductionism, especially in the face of human striving and objective progress. But therein also lies the power to be able to turn certainty on its head—by knowing how it goes, one can crack the code towards change.

As it will be revealed in the end, The Insect Woman shows that in a sense, what seems to be the only way can also be the way out.